June 2018 Presentation for Multi Academy Trusts

Earlier this week I attended an important event hosted by Inside Government called Raising Standards through Multi Academy Trust Inspections. Speaking at the event was great motivation to stop and reflect on what we’ve learned about shared vision for school improvement and accountability over the past few years at Edurio and what lessons would be valuable for multi academy trust teams (especially thinking ahead to future MAT inspections).

The debate that followed the session with many MAT leaders led me to believe that these lessons are useful in a variety of education settings, so I’ve typed up the talk for your enjoyment. While the talk is focusing on multi academy trusts, the lessons remain relevant for most school systems.

When I was thinking about the event, something struck me as odd. The name, “Raising Standards through Multi Academy Trust Inspections”. I think everyone would agree it’s not the inspections that raises the standard. It’s the hard work done by trusts, by schools, by teachers.

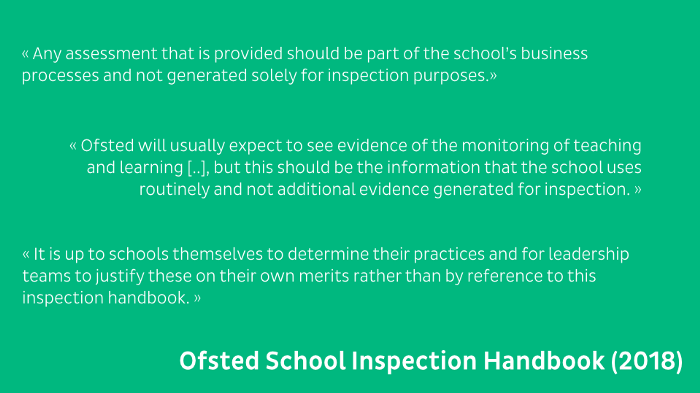

Ofsted is not looking for trusts or for schools to prepare inspection-driven procedures. This is mirrored throughout the Ofsted School Inspection Handbook:

Seeing many school inspection approaches through our work with Edurio across Europe, it’s clear that the ideal for good school inspections is to be school improvement partner, rather than a mechanism for compliance or control.

So rather than talking about compliance, I want to talk about lessons on school improvement we’ve seen internationally that, when done well, lead to better preparation for inspections.

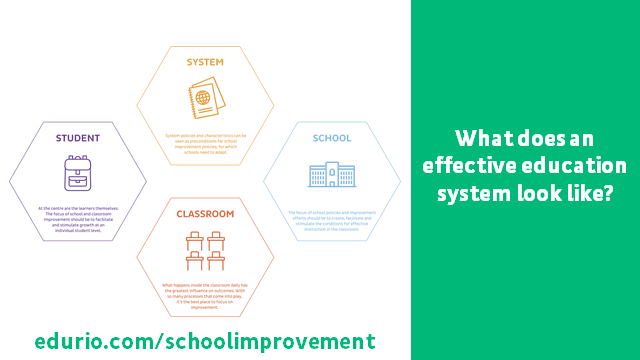

Striking the Balance: Navigating Top-Down Control and School Autonomy in Effective School Improvement Policies

A key problem for many school systems in implementing a coherent school improvement policy is finding a balance between top down control and school autonomy. You don’t want to dictate every process in the school — every school is different. School leaders understand their needs and priorities much better than you do. You want them to make the right day-to-day decisions, but you also want accountability, central support and collaboration to ensure standards.

The answer is neither top-down management, nor a hands-off approach. A good process is getting the best of both worlds — a shared vision with school-driven improvement. Shared vision, shared objectives, shared strategies across the entire school system, with each school implementing them, taking into account their unique local context.

But how do we get there?

First, a vision of school improvement that is embedded in an organisation’s culture.

A lot of time is invested into defining what a trust stands for, how you think about quality. But how many can honestly say that the vision is shared and truly lived by students and teachers across all of the trust’s schools? Especially now that visions focus more and more on factors other than academic outputs — like collaboration or innovation. These sound nice, but does everybody really understand what they mean? How can you know that they are working for everybody and interpreted by everybody in the same way?

Empowering Pupil Voice: Collaborative Design with United Learning

We’ve been helping United Learning design a pupil voice process focused on their Framework of Excellence. This allows them to turn a conceptual framework into a very actionable toolkit for each school, and makes their vision, their values integrated and aligned with the schools’ work.

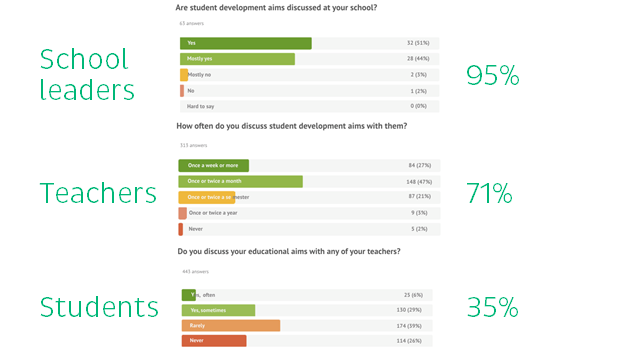

Another example. We did a school culture study with the Ministry of Education of Latvia. We asked different stakeholders whether there is a culture of discussing student development aims across a 60 schools. 95% of principals said aims are being discussed, 71% teachers agreed but only a third of students felt they discuss their aims with teachers.

This doesn’t mean that someone is lying. We all interpret the same concepts differently. Just because a vision is written on a website, doesn’t mean it’s understood in the same way by everyone. We need to work very hard on communicating our vision and values to the people who will be living them.

This is very hard work, especially as you have new schools joining the trust with a different culture, but you can’t have a shared improvement approach if you don’t have a shared vision of what you’re improving towards.

Second, you need to measure what matters.

Let’s talk for a minute about health and fitness. We have all come to realise that hopping on the scale each day doesn’t do much to improve our level of fitness. It doesn’t tell you much does it? Is your current fitness programme working? Are you gaining muscle or fat? What can I do today to change the number tomorrow?

Nowadays, you can get yourself an activity tracker. Products like Fitbit track all the little things that affect your fitness each day — how many steps you take, how many calories you burn, how many hours you sleep — and give you the extra motivation of attainable daily targets.

Assessment data is like the scale — it’s only looking at the end result, not all the factors that lead to the result. You need to understand the daily education processes that lead to those academic outcomes.

In a recent critical MAT review Ofsted said: “At times, they are not sufficiently accurate in their analysis of data or precise enough about what needs to improve.”

You are expected to know your schools, know what steps must be taken to improve, what processes you could change today that will boost those performance numbers in the future.

We’re actually in an extremely data-rich time. But we are insight-poor.

There is a lot of research out there on measuring the education process. That’s why we teamed up with the UCL Institute of Education team to map out the factors that research tells us lead to improved academic outcomes. We are now designing a survey bank to allow for continuous measurement of those factors in a way that is research based and aligns with Ofsted requirements.

Third, your school improvement process needs to put schools in the driving seat

Many of you will have either strong internal quality teams or a network of external experts. That’s great, but it can’t replace capacity building in the school, as the schools need to own improvement for it to be sustainable.

But how do you create a process that works? That’s a topic so vast that you could literally write a book about it… so we did. I hope this is of value to you as your role is to set up a sustainable process rather than just helping fix the issue of the day.

Forth, unlocking school collaboration

Another phrase that is thrown around a lot but not that easy to get right.

I think Mark Goodchild summed it up very well when he said that in order to have true school collaboration you need three factors:

Infrastructure — time and capability for schools to meet and work together on their improvement priorities

Incentives — whether financial or status, to give everybody a clear benefit from collaborating

Trust — talking about improvement needs is difficult if there isn’t trust that the process and central team are there to help improvement rather than to control.

Too many organisations focus entirely on infrastructure and then fail to see good collaboration happen. Your role is setting up sustainable processes for collaboration to happen at every level and establishing the right culture and values so people feel comfortable giving and receiving feedback, talking about challenges and asking for help.

And that leads to my last point:

You have to rethink how you engage with stakeholders. How you get their feedback and learn from them.

Stakeholder feedback is important across everything I’ve shared today.

- Collecting feedback helps you communicate and understand how your vision is interpreted and practiced across a growing number of schools.

- Getting targeted feedback measures what matters and helps you better understand the educational experience in each school.

- Schools must learn from their stakeholders in driving their own improvement.

- Building a culture of feedback, and setting up mechanisms for regular exchange of feedback, opens the door for collaboration.

Now I’m not just here to tell you that stakeholder feedback is important. You know that. Ofsted knows that. Unfortunately, having seen stakeholder feedback processes in hundreds of schools, I can say that most are getting very little value from the process.

And that’s because there is a problem at the core of the process. Stakeholder feedback is seen as just another metric to improve so it becomes a burden, adding to workload with little to no clear benefit.

In reality, the feedback you collect should be directly tied to your priorities and inform your decisions. Instead of gauging satisfaction, you should capture insights in the education process. Instead of improving feedback, you should use feedback to improve education.

That was our vision when launching Edurio four years ago. After talking to schools and school system leaders from five continents, we believe that fixing stakeholder feedback unlocks a lot of improvement capability in schools.

So these are the 5 lessons we’ve had in setting up a system-wide school improvement process. Having a positive inspection is first and foremost about being a good, improvement focused organisation. Thank you!

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020SME programme for open and disruptive innovation under grant agreement №733984.

No comments.